Getting Started with the RDKit in Python¶

Important note¶

Beginning with the 2019.03 release, the RDKit is no longer supporting Python 2. If you need to continue using Python 2, please stick with a release from the 2018.09 release cycle.

What is this?¶

This document is intended to provide an overview of how one can use the RDKit functionality from Python. It’s not comprehensive and it’s not a manual.

If you find mistakes, or have suggestions for improvements, please either fix them yourselves in the source document (the .rst file) or send them to the mailing list: rdkit-devel@lists.sourceforge.net In particular, if you find yourself spending time working out how to do something that doesn’t appear to be documented please contribute by writing it up for this document. Contributing to the documentation is a great service both to the RDKit community and to your future self.

Reading, Drawing, and Writing Molecules¶

Reading single molecules¶

The majority of the basic molecular functionality is found in module rdkit.Chem:

>>> from rdkit import Chem

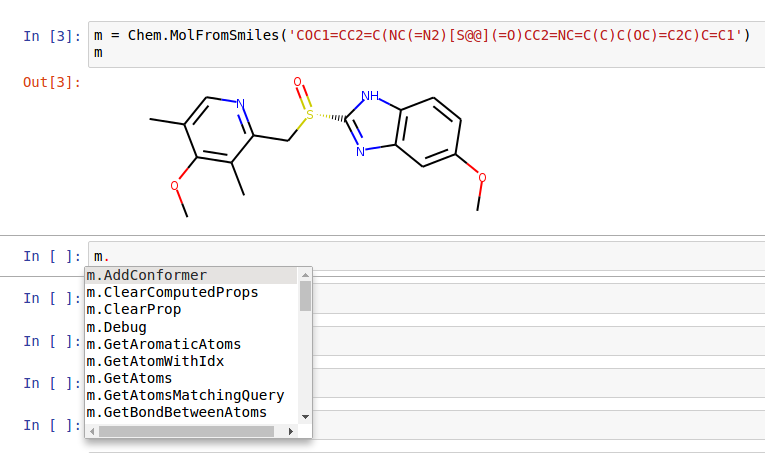

Individual molecules can be constructed using a variety of approaches:

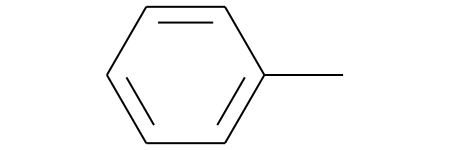

>>> m = Chem.MolFromSmiles('Cc1ccccc1')

>>> m = Chem.MolFromMolFile('data/input.mol')

>>> stringWithMolData=open('data/input.mol','r').read()

>>> m = Chem.MolFromMolBlock(stringWithMolData)

All of these functions return a rdkit.Chem.rdchem.Mol object on success:

>>> m

<rdkit.Chem.rdchem.Mol object at 0x...>

or None on failure:

>>> m_invalid = Chem.MolFromMolFile('data/invalid.mol')

>>> m_invalid is None

True

An rdkit.Chem.rdchem.Mol object can be displayed graphically using rdkit.Chem.Draw.MolToImage():

>>> from rdkit.Chem import Draw

>>> img = Draw.MolToImage(m)

An attempt is made to provide sensible error messages:

>>> m1 = Chem.MolFromSmiles('CO(C)C')

displays a message like: [12:18:01] Explicit valence for atom # 1 O greater than permitted and

>>> m2 = Chem.MolFromSmiles('c1cc1')

displays something like: [12:20:41] Can't kekulize mol. In each case the value None is returned:

>>> m1 is None

True

>>> m2 is None

True

Reading sets of molecules¶

Groups of molecules are read using a Supplier (for example, an rdkit.Chem.rdmolfiles.SDMolSupplier or a rdkit.Chem.rdmolfiles.SmilesMolSupplier):

>>> suppl = Chem.SDMolSupplier('data/5ht3ligs.sdf')

>>> for mol in suppl:

... print(mol.GetNumAtoms())

...

20

24

24

26

You can easily produce lists of molecules from a Supplier:

>>> mols = [x for x in suppl]

>>> len(mols)

4

or just treat the Supplier itself as a random-access object:

>>> suppl[0].GetNumAtoms()

20

Two good practices when working with Suppliers are to use a context manager and to test each molecule to see if it was correctly read before working with it:

>>> with Chem.SDMolSupplier('data/5ht3ligs.sdf') as suppl:

... for mol in suppl:

... if mol is None: continue

... print(mol.GetNumAtoms())

...

20

24

24

26

An alternate type of Supplier, the rdkit.Chem.rdmolfiles.ForwardSDMolSupplier

can be used to read from file-like objects:

>>> inf = open('data/5ht3ligs.sdf','rb')

>>> with Chem.ForwardSDMolSupplier(inf) as fsuppl:

... for mol in fsuppl:

... if mol is None: continue

... print(mol.GetNumAtoms())

...

20

24

24

26

This means that they can be used to read from compressed files:

>>> import gzip

>>> inf = gzip.open('data/actives_5ht3.sdf.gz')

>>> with Chem.ForwardSDMolSupplier(inf) as gzsuppl:

... ms = [x for x in gzsuppl if x is not None]

>>> len(ms)

180

Note that ForwardSDMolSuppliers cannot be used as random-access objects:

>>> inf = open('data/5ht3ligs.sdf','rb')

>>> with Chem.ForwardSDMolSupplier(inf) as fsuppl:

... fsuppl[0]

Traceback (most recent call last):

...

TypeError: 'ForwardSDMolSupplier' object does not support indexing

For reading Smiles or SDF files with large number of records concurrently, MultithreadedMolSuppliers can be used like this:

>>> i = 0

>>> with Chem.MultithreadedSDMolSupplier('data/5ht3ligs.sdf') as sdSupl:

... for mol in sdSupl:

... if mol is not None:

... i += 1

...

>>> print(i)

4

By default a single reader thread is used to extract records from the file and a single writer thread is used to process them. Note that due to multithreading the output may not be in the expected order. Furthermore, the MultithreadedSmilesMolSupplier and the MultithreadedSDMolSupplier cannot be used as random-access objects.

Writing molecules¶

Single molecules can be converted to text using several functions present in the rdkit.Chem module.

For example, for SMILES:

>>> m = Chem.MolFromMolFile('data/chiral.mol')

>>> Chem.MolToSmiles(m)

'C[C@H](O)c1ccccc1'

>>> Chem.MolToSmiles(m,isomericSmiles=False)

'CC(O)c1ccccc1'

Note that the SMILES provided is canonical, so the output should be the same no matter how a particular molecule is input:

>>> Chem.MolToSmiles(Chem.MolFromSmiles('C1=CC=CN=C1'))

'c1ccncc1'

>>> Chem.MolToSmiles(Chem.MolFromSmiles('c1cccnc1'))

'c1ccncc1'

>>> Chem.MolToSmiles(Chem.MolFromSmiles('n1ccccc1'))

'c1ccncc1'

If you’d like to have the Kekule form of the SMILES, first Kekulize the molecule, then use the “kekuleSmiles” option:

>>> Chem.Kekulize(m)

>>> Chem.MolToSmiles(m,kekuleSmiles=True)

'C[C@H](O)C1=CC=CC=C1'

Note: as of this writing (Aug 2008), the smiles provided when one requests kekuleSmiles are not canonical. The limitation is not in the SMILES generation, but in the kekulization itself.

MDL Mol blocks are also available:

>>> m2 = Chem.MolFromSmiles('C1CCC1')

>>> print(Chem.MolToMolBlock(m2))

RDKit 2D

4 4 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0999 V2000

1.0607 0.0000 0.0000 C 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0

-0.0000 -1.0607 0.0000 C 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0

-1.0607 0.0000 0.0000 C 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0

0.0000 1.0607 0.0000 C 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0

1 2 1 0

2 3 1 0

3 4 1 0

4 1 1 0

M END

To include names in the mol blocks, set the molecule’s “_Name” property:

>>> m2.SetProp("_Name","cyclobutane")

>>> print(Chem.MolToMolBlock(m2))

cyclobutane

RDKit 2D

4 4 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0999 V2000

1.0607 0.0000 0.0000 C 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0

-0.0000 -1.0607 0.0000 C 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0

-1.0607 0.0000 0.0000 C 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0

0.0000 1.0607 0.0000 C 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0

1 2 1 0

2 3 1 0

3 4 1 0

4 1 1 0

M END

In order for atom or bond stereochemistry to be recognised correctly by most

software, it’s essential that the mol block have atomic coordinates.

It’s also convenient for many reasons, such as drawing the molecules.

Generating a mol block for a molecule that does not have coordinates will, by

default, automatically cause coordinates to be generated. These are not,

however, stored with the molecule.

Coordinates can be generated and stored with the molecule using functionality

in the rdkit.Chem.AllChem module (see the Chem vs AllChem section for

more information).

You can either include 2D coordinates (i.e. a depiction):

>>> from rdkit.Chem import AllChem

>>> AllChem.Compute2DCoords(m2)

0

>>> print(Chem.MolToMolBlock(m2))

cyclobutane

RDKit 2D

4 4 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0999 V2000

1.0607 -0.0000 0.0000 C 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0

-0.0000 -1.0607 0.0000 C 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0

-1.0607 0.0000 0.0000 C 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0

0.0000 1.0607 0.0000 C 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0

1 2 1 0

2 3 1 0

3 4 1 0

4 1 1 0

M END

Or you can add 3D coordinates by embedding the molecule (this uses the ETKDG method, which is described in more detail below). Note that we add Hs to the molecule before generating the conformer. This is essential to get good structures:

>>> m3 = Chem.AddHs(m2)

>>> params = AllChem.ETKDGv3()

>>> params.randomSeed = 0xf00d # optional random seed for reproducibility

>>> AllChem.EmbedMolecule(m3, params)

0

>>> print(Chem.MolToMolBlock(m3))

cyclobutane

RDKit 3D

12 12 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0999 V2000

1.0257 0.2442 -0.0991 C 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0

-0.2041 0.9236 0.4320 C 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0

-1.0443 -0.2424 -0.0253 C 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0

0.2102 -0.9939 -0.3417 C 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0

1.4192 0.7683 -0.9787 H 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0

1.8181 0.1486 0.6820 H 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0

-0.1697 1.0826 1.5236 H 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0

-0.5360 1.8377 -0.1050 H 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0

-1.6809 -0.0600 -0.8987 H 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0

-1.6510 -0.6193 0.8225 H 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0

0.4659 -1.7768 0.3858 H 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0

0.3467 -1.3126 -1.3975 H 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0

1 2 1 0

2 3 1 0

3 4 1 0

4 1 1 0

1 5 1 0

1 6 1 0

2 7 1 0

2 8 1 0

3 9 1 0

3 10 1 0

4 11 1 0

4 12 1 0

M END

If we don’t want the Hs in our later analysis, they are easy to remove:

>>> m3 = Chem.RemoveHs(m3)

>>> print(Chem.MolToMolBlock(m3))

cyclobutane

RDKit 3D

4 4 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0999 V2000

1.0257 0.2442 -0.0991 C 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0

-0.2041 0.9236 0.4320 C 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0

-1.0443 -0.2424 -0.0253 C 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0

0.2102 -0.9939 -0.3417 C 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0

1 2 1 0

2 3 1 0

3 4 1 0

4 1 1 0

M END

If you’d like to write the molecule to a file, use Python file objects:

>>> print(Chem.MolToMolBlock(m2),file=open('data/foo.mol','w+'))

>>>

Writing sets of molecules¶

Multiple molecules can be written to a file using an rdkit.Chem.rdmolfiles.SDWriter object:

>>> with Chem.SDWriter('data/foo.sdf') as w:

... for m in mols:

... w.write(m)

>>>

An SDWriter can also be initialized using a file-like object:

>>> from io import StringIO

>>> sio = StringIO()

>>> with Chem.SDWriter(sio) as w:

... for m in mols:

... w.write(m)

>>> print(sio.getvalue())

mol-295

RDKit 3D

20 22 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 0999 V2000

2.3200 0.0800 -0.1000 C 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0

1.8400 -1.2200 0.1200 C 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0

...

1 3 1 0

1 4 1 0

2 5 1 0

M END

$$$$

Other available Writers include the rdkit.Chem.rdmolfiles.SmilesWriter and the rdkit.Chem.rdmolfiles.TDTWriter.

Working with Molecules¶

Looping over Atoms and Bonds¶

Once you have a molecule, it’s easy to loop over its atoms and bonds:

>>> m = Chem.MolFromSmiles('C1OC1')

>>> for atom in m.GetAtoms():

... print(atom.GetAtomicNum())

...

6

8

6

>>> print(m.GetBonds()[0].GetBondType())

SINGLE

You can also request individual bonds or atoms:

>>> m.GetAtomWithIdx(0).GetSymbol()

'C'

>>> m.GetAtomWithIdx(0).GetExplicitValence()

2

>>> m.GetBondWithIdx(0).GetBeginAtomIdx()

0

>>> m.GetBondWithIdx(0).GetEndAtomIdx()

1

>>> m.GetBondBetweenAtoms(0,1).GetBondType()

rdkit.Chem.rdchem.BondType.SINGLE

Atoms keep track of their neighbors:

>>> atom = m.GetAtomWithIdx(0)

>>> [x.GetAtomicNum() for x in atom.GetNeighbors()]

[8, 6]

>>> len(atom.GetNeighbors()[-1].GetBonds())

2

Ring Information¶

Atoms and bonds both carry information about the molecule’s rings:

>>> m = Chem.MolFromSmiles('OC1C2C1CC2')

>>> m.GetAtomWithIdx(0).IsInRing()

False

>>> m.GetAtomWithIdx(1).IsInRing()

True

>>> m.GetAtomWithIdx(2).IsInRingSize(3)

True

>>> m.GetAtomWithIdx(2).IsInRingSize(4)

True

>>> m.GetAtomWithIdx(2).IsInRingSize(5)

False

>>> m.GetBondWithIdx(1).IsInRingSize(3)

True

>>> m.GetBondWithIdx(1).IsInRing()

True

But note that the information is only about the smallest rings:

>>> m.GetAtomWithIdx(1).IsInRingSize(5)

False

More detail about the smallest set of smallest rings (SSSR) is available:

>>> ssr = Chem.GetSymmSSSR(m)

>>> len(ssr)

2

>>> list(ssr[0])

[1, 2, 3]

>>> list(ssr[1])

[4, 5, 2, 3]

As the name indicates, this is a symmetrized SSSR; if you are interested in the number of “true” SSSR, use the GetSSSR function (note that in this case there’s no difference).

>>> len(Chem.GetSSSR(m))

2

The distinction between symmetrized and non-symmetrized SSSR is discussed in more detail below in the section The SSSR Problem.

For more efficient queries about a molecule’s ring systems (avoiding repeated calls to Mol.GetAtomWithIdx), use the rdkit.Chem.rdchem.RingInfo class:

>>> m = Chem.MolFromSmiles('OC1C2C1CC2')

>>> ri = m.GetRingInfo()

>>> ri.NumAtomRings(0)

0

>>> ri.NumAtomRings(1)

1

>>> ri.NumAtomRings(2)

2

>>> ri.IsAtomInRingOfSize(1,3)

True

>>> ri.IsBondInRingOfSize(1,3)

True

Modifying molecules¶

Normally molecules are stored in the RDKit with the hydrogen atoms implicit (e.g. not explicitly present in the molecular graph. When it is useful to have the hydrogens explicitly present, for example when generating or optimizing the 3D geometry, the :py:func:rdkit.Chem.rdmolops.AddHs function can be used:

>>> m=Chem.MolFromSmiles('CCO')

>>> m.GetNumAtoms()

3

>>> m2 = Chem.AddHs(m)

>>> m2.GetNumAtoms()

9

The Hs can be removed again using the rdkit.Chem.rdmolops.RemoveHs() function:

>>> m3 = Chem.RemoveHs(m2)

>>> m3.GetNumAtoms()

3

RDKit molecules are usually stored with the bonds in aromatic rings having aromatic bond types.

This can be changed with the rdkit.Chem.rdmolops.Kekulize() function:

>>> m = Chem.MolFromSmiles('c1ccccc1')

>>> m.GetBondWithIdx(0).GetBondType()

rdkit.Chem.rdchem.BondType.AROMATIC

>>> Chem.Kekulize(m)

>>> m.GetBondWithIdx(0).GetBondType()

rdkit.Chem.rdchem.BondType.DOUBLE

>>> m.GetBondWithIdx(1).GetBondType()

rdkit.Chem.rdchem.BondType.SINGLE

By default, the bonds are still marked as being aromatic:

>>> m.GetBondWithIdx(1).GetIsAromatic()

True

because the flags in the original molecule are not cleared (clearAromaticFlags defaults to False). You can explicitly force or decline a clearing of the flags:

>>> m = Chem.MolFromSmiles('c1ccccc1')

>>> m.GetBondWithIdx(0).GetIsAromatic()

True

>>> m1 = Chem.MolFromSmiles('c1ccccc1')

>>> Chem.Kekulize(m1, clearAromaticFlags=True)

>>> m1.GetBondWithIdx(0).GetIsAromatic()

False

Bonds can be restored to the aromatic bond type using the rdkit.Chem.rdmolops.SanitizeMol() function:

>>> Chem.SanitizeMol(m)

rdkit.Chem.rdmolops.SanitizeFlags.SANITIZE_NONE

>>> m.GetBondWithIdx(0).GetBondType()

rdkit.Chem.rdchem.BondType.AROMATIC

The value returned by SanitizeMol() indicates that no problems were encountered.

Working with 2D molecules: Generating Depictions¶

The RDKit has a library for generating depictions (sets of 2D) coordinates for molecules.

This library, which is part of the AllChem module, is accessed using the rdkit.Chem.rdDepictor.Compute2DCoords() function:

>>> m = Chem.MolFromSmiles('c1nccc2n1ccc2')

>>> AllChem.Compute2DCoords(m)

0

The 2D conformer is constructed in a canonical orientation and is built to minimize intramolecular clashes, i.e. to maximize the clarity of the drawing.

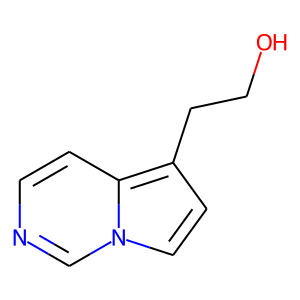

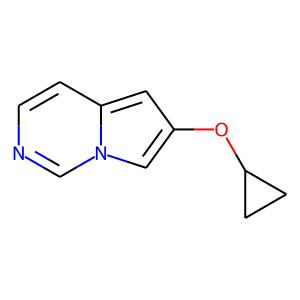

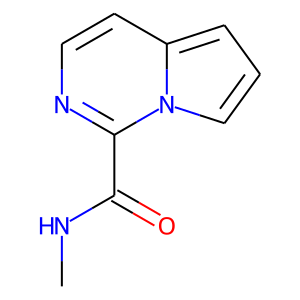

If you have a set of molecules that share a common template and you’d like to align them to that template, you can do so as follows:

>>> template = Chem.MolFromSmiles('c1nccc2n1ccc2')

>>> AllChem.Compute2DCoords(template)

0

>>> ms = [Chem.MolFromSmiles(smi) for smi in ('OCCc1ccn2cnccc12','C1CC1Oc1cc2ccncn2c1','CNC(=O)c1nccc2cccn12')]

>>> for m in ms:

... _ = AllChem.GenerateDepictionMatching2DStructure(m,template)

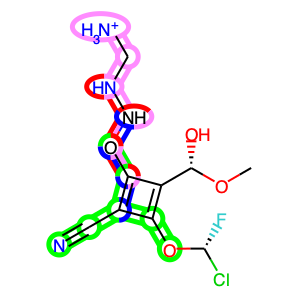

Running this process for the molecules above gives:

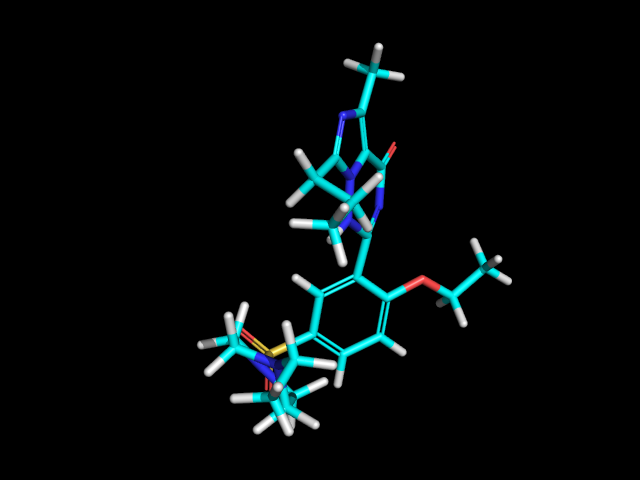

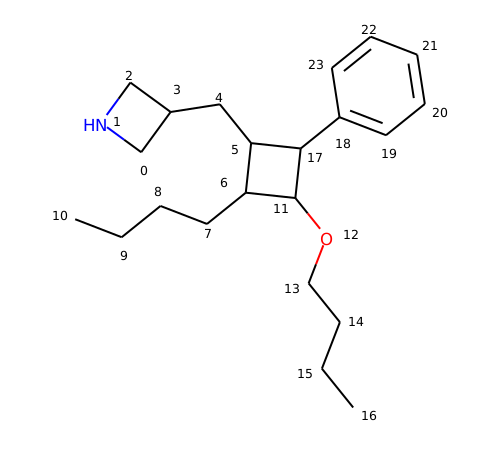

Another option for Compute2DCoords allows you to generate 2D depictions for molecules that closely mimic 3D conformers.

This is available using the function rdkit.Chem.AllChem.GenerateDepictionMatching3DStructure().

Here is an illustration of the results using the ligand from PDB structure 1XP0:

More fine-grained control can be obtained using the core function

rdkit.Chem.rdDepictor.Compute2DCoordsMimicDistmat(), but that is

beyond the scope of this document. See the implementation of

GenerateDepictionMatching3DStructure in AllChem.py for an example of

how it is used.

Working with 3D Molecules¶

The RDKit can generate conformers for molecules using two different methods. The original method used distance geometry. [1] The algorithm followed is:

The molecule’s distance bounds matrix is calculated based on the connection table and a set of rules.

The bounds matrix is smoothed using a triangle-bounds smoothing algorithm.

A random distance matrix that satisfies the bounds matrix is generated.

This distance matrix is embedded in 3D dimensions (producing coordinates for each atom).

The resulting coordinates are cleaned up somewhat using a crude force field and the bounds matrix.

Note that the conformers that result from this procedure tend to be fairly ugly. They should be cleaned up using a force field. This can be done within the RDKit using its implementation of the Universal Force Field (UFF). [2]

More recently, there is an implementation of the ETKDG method of Riniker and Landrum [18] which uses torsion angle preferences from the Cambridge Structural Database (CSD) to correct the conformers after distance geometry has been used to generate them. With this method, there should be no need to use a minimisation step to clean up the structures.

More detailed information about the conformer generator and the parameters controlling it can be found in the “RDKit Book”.

Since the 2018.09 release of the RDKit, ETKDG is the default conformer generation method. Since the 2024.03 release ETKDGv3 is the default.

The full process of embedding a molecule is easier than all the above verbiage makes it sound:

>>> m2=Chem.AddHs(m)

>>> AllChem.EmbedMolecule(m2)

0

The RDKit also has an implementation of the MMFF94 force field available. [12], [13], [14], [15], [16] Please note that the MMFF atom typing code uses its own aromaticity model, so the aromaticity flags of the molecule will be modified after calling MMFF-related methods.

Here’s an example of using MMFF94 to minimize an RDKit-generated conformer: .. doctest:

>>> m = Chem.MolFromSmiles('C1CCC1OC')

>>> m2=Chem.AddHs(m)

>>> AllChem.EmbedMolecule(m2)

0

>>> AllChem.MMFFOptimizeMolecule(m2)

0

Note the calls to Chem.AddHs() in the examples above. By default RDKit molecules do not have H atoms explicitly present in the graph, but they are important for getting realistic geometries, so they generally should be added. They can always be removed afterwards if necessary with a call to Chem.RemoveHs().

With the RDKit, multiple conformers can also be generated using the different embedding methods. In both cases this is simply a matter of running the distance geometry calculation multiple times from different random start points. The option numConfs allows the user to set the number of conformers that should be generated. Otherwise the procedures are as before. The conformers so generated can be aligned to each other and the RMS values calculated.

>>> m = Chem.MolFromSmiles('C1CCC1OC')

>>> m2=Chem.AddHs(m)

>>> # run ETKDG 10 times

>>> cids = AllChem.EmbedMultipleConfs(m2, numConfs=10)

>>> print(len(cids))

10

>>> rmslist = []

>>> AllChem.AlignMolConformers(m2, RMSlist=rmslist)

>>> print(len(rmslist))

9

rmslist contains the RMS values between the first conformer and all others. The RMS between two specific conformers (e.g. 1 and 9) can also be calculated. The flag prealigned lets the user specify if the conformers are already aligned (by default, the function aligns them).

>>> rms = AllChem.GetConformerRMS(m2, 1, 9, prealigned=True)

If you are interested in running MMFF94 on a molecule’s conformers (note that this is often not necessary when using ETKDG), there’s a convenience function available:

>>> res = AllChem.MMFFOptimizeMoleculeConfs(m2)

The result is a list a containing 2-tuples: (not_converged, energy) for each conformer. If not_converged is 0, the minimization for that conformer converged.

By default AllChem.EmbedMultipleConfs and AllChem.MMFFOptimizeMoleculeConfs() run single threaded, but you can cause them to use multiple threads simultaneously for these embarassingly parallel tasks via the numThreads argument:

>>> params = AllChem.ETKDGv3()

>>> params.numThreads = 0

>>> cids = AllChem.EmbedMultipleConfs(m2, 10, params)

>>> res = AllChem.MMFFOptimizeMoleculeConfs(m2, numThreads=0)

Setting numThreads to zero causes the software to use the maximum number of threads allowed on your computer.

Disclaimer/Warning: Conformer generation is a difficult and subtle task. The plain distance-geometry 2D->3D conversion provided with the RDKit is not intended to be a replacement for a “real” conformer analysis tool; it merely provides quick 3D structures for cases when they are required. We believe, however, that the newer ETKDG method [18] is suitable for most purposes.

Preserving Molecules¶

Molecules can be converted to and from text using Python’s pickling machinery:

>>> m = Chem.MolFromSmiles('c1ccncc1')

>>> import pickle

>>> pkl = pickle.dumps(m)

>>> m2=pickle.loads(pkl)

>>> Chem.MolToSmiles(m2)

'c1ccncc1'

The RDKit pickle format is fairly compact and it is much, much faster to build a molecule from a pickle than from a Mol file or SMILES string, so storing molecules you will be working with repeatedly as pickles can be a good idea.

The raw binary data that is encapsulated in a pickle can also be directly obtained from a molecule:

>>> binStr = m.ToBinary()

This can be used to reconstruct molecules using the Chem.Mol constructor:

>>> m2 = Chem.Mol(binStr)

>>> Chem.MolToSmiles(m2)

'c1ccncc1'

>>> len(binStr)

130

Note that this is smaller than the pickle:

>>> len(binStr) < len(pkl)

True

The small overhead associated with python’s pickling machinery normally doesn’t end up making much of a difference for collections of larger molecules (the extra data associated with the pickle is independent of the size of the molecule, while the binary string increases in length as the molecule gets larger).

Tip: The performance difference associated with storing molecules in a pickled form on disk instead of constantly reparsing an SD file or SMILES table is difficult to overstate. In a test I just ran on my laptop, loading a set of 699 drug-like molecules from an SD file took 10.8 seconds; loading the same molecules from a pickle file took 0.7 seconds. The pickle file is also smaller – 1/3 the size of the SD file – but this difference is not always so dramatic (it’s a particularly fat SD file).

Drawing Molecules¶

The RDKit has some built-in functionality for creating images from

molecules found in the rdkit.Chem.Draw package:

>>> with Chem.SDMolSupplier('data/cdk2.sdf') as suppl:

... ms = [x for x in suppl if x is not None]

>>> for m in ms: tmp=AllChem.Compute2DCoords(m)

>>> from rdkit.Chem import Draw

>>> Draw.MolToFile(ms[0],'images/cdk2_mol1.o.png')

>>> Draw.MolToFile(ms[1],'images/cdk2_mol2.o.png')

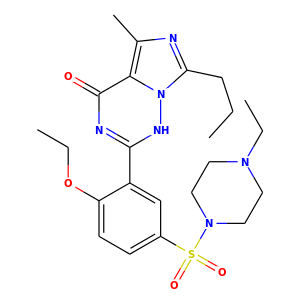

Producing these images:

|

|

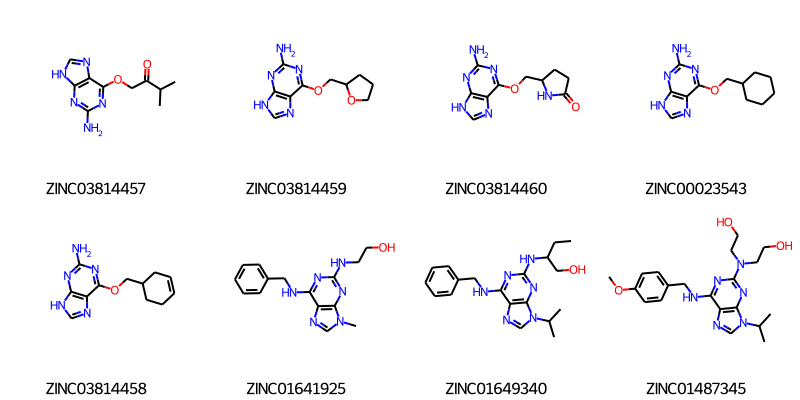

It’s also possible to produce an image grid out of a set of molecules:

>>> img=Draw.MolsToGridImage(ms[:8],molsPerRow=4,subImgSize=(200,200),legends=[x.GetProp("_Name") for x in ms[:8]])

This returns a PIL image, which can then be saved to a file:

>>> img.save('images/cdk2_molgrid.o.png')

The result looks like this:

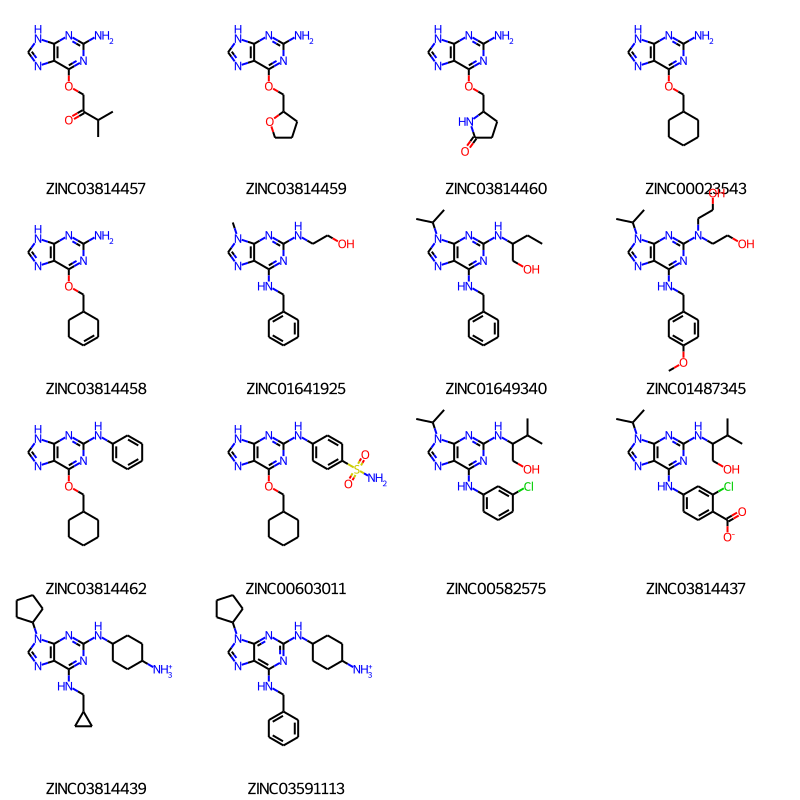

These would of course look better if the common core were aligned. This is easy enough to do:

>>> p = Chem.MolFromSmiles('[nH]1cnc2cncnc21')

>>> subms = [x for x in ms if x.HasSubstructMatch(p)]

>>> len(subms)

14

>>> AllChem.Compute2DCoords(p)

0

>>> for m in subms:

... _ = AllChem.GenerateDepictionMatching2DStructure(m,p)

>>> img=Draw.MolsToGridImage(subms,molsPerRow=4,subImgSize=(200,200),legends=[x.GetProp("_Name") for x in subms])

>>> img.save('images/cdk2_molgrid.aligned.o.png')

The result looks like this:

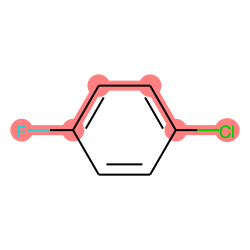

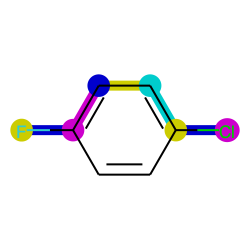

Atoms in a molecule can be highlighted by drawing a coloured solid or open circle around them, and bonds likewise can have a coloured outline applied. An obvious use is to show atoms and bonds that have matched a substructure query

>>> from rdkit.Chem.Draw import rdMolDraw2D

>>> smi = 'c1cc(F)ccc1Cl'

>>> mol = Chem.MolFromSmiles(smi)

>>> patt = Chem.MolFromSmarts('ClccccF')

>>> hit_ats = list(mol.GetSubstructMatch(patt))

>>> hit_bonds = []

>>> for bond in patt.GetBonds():

... aid1 = hit_ats[bond.GetBeginAtomIdx()]

... aid2 = hit_ats[bond.GetEndAtomIdx()]

... hit_bonds.append(mol.GetBondBetweenAtoms(aid1,aid2).GetIdx())

>>> d = rdMolDraw2D.MolDraw2DSVG(500, 500) # or MolDraw2DCairo to get PNGs

>>> rdMolDraw2D.PrepareAndDrawMolecule(d, mol, highlightAtoms=hit_ats,

... highlightBonds=hit_bonds)

will produce:

It is possible to specify the colours for individual atoms and bonds:

>>> colours = [(0.8,0.0,0.8),(0.8,0.8,0),(0,0.8,0.8),(0,0,0.8)]

>>> atom_cols = {}

>>> for i, at in enumerate(hit_ats):

... atom_cols[at] = colours[i%4]

>>> bond_cols = {}

>>> for i, bd in enumerate(hit_bonds):

... bond_cols[bd] = colours[3 - i%4]

>>>

>>> d = rdMolDraw2D.MolDraw2DCairo(500, 500)

>>> rdMolDraw2D.PrepareAndDrawMolecule(d, mol, highlightAtoms=hit_ats,

... highlightAtomColors=atom_cols,

... highlightBonds=hit_bonds,

... highlightBondColors=bond_cols)

to give:

Atoms and bonds can also be highlighted with multiple colours if they fall into multiple sets, for example if they are matched by more than 1 substructure pattern. This is too complicated to show in this simple introduction, but there is an example in data/test_multi_colours.py, which produces the somewhat garish

As of version 2020.03, it is possible to add arbitrary small strings to annotate

atoms and bonds in the drawing. The strings are added as properties

atomNote and bondNote and they will be placed automatically close to the

atom or bond in question in a manner intended to minimise their clash with the

rest of the drawing. For convenience, here are 3 flags in MolDraw2DOptions

that will add stereo information (R/S to atoms, E/Z to bonds) and atom and bond

sequence numbers.

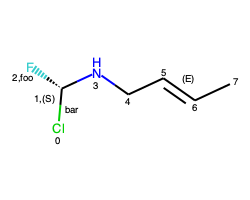

>>> mol = Chem.MolFromSmiles(r'Cl[C@H](F)NC\C=C\C')

>>> d = rdMolDraw2D.MolDraw2DCairo(250, 200) # or MolDraw2DSVG to get SVGs

>>> mol.GetAtomWithIdx(2).SetProp('atomNote', 'foo')

>>> mol.GetBondWithIdx(0).SetProp('bondNote', 'bar')

>>> d.drawOptions().addStereoAnnotation = True

>>> d.drawOptions().addAtomIndices = True

>>> d.DrawMolecule(mol)

>>> d.FinishDrawing()

>>> d.WriteDrawingText('atom_annotation_1.png')

will produce

If atoms have an atomLabel property set, this will be used when drawing them:

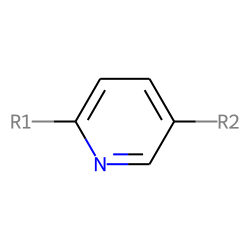

>>> smi = 'c1nc(*)ccc1* |$;;;R1;;;;R2$|'

>>> mol = Chem.MolFromSmiles(smi)

>>> mol.GetAtomWithIdx(3).GetProp("atomLabel")

'R1'

>>> mol.GetAtomWithIdx(7).GetProp("atomLabel")

'R2'

>>> d = rdMolDraw2D.MolDraw2DCairo(250, 250)

>>> rdMolDraw2D.PrepareAndDrawMolecule(d,mol)

>>> d.WriteDrawingText("./images/atom_labels_1.png")

gives:

Since the atomLabel property is also used for other things (for example in CXSMILES as demonstrated),

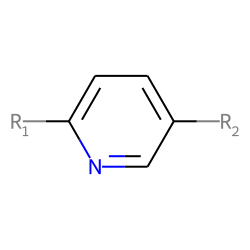

if you want to provide your own atom labels, it’s better to use the _displayLabel property:

>>> smi = 'c1nc(*)ccc1* |$;;;R1;;;;R2$|'

>>> mol = Chem.MolFromSmiles(smi)

>>> mol.GetAtomWithIdx(3).SetProp("_displayLabel","R<sub>1</sub>")

>>> mol.GetAtomWithIdx(7).SetProp("_displayLabel","R<sub>2</sub>")

>>> d = rdMolDraw2D.MolDraw2DCairo(250, 250)

>>> rdMolDraw2D.PrepareAndDrawMolecule(d,mol)

>>> d.WriteDrawingText("./images/atom_labels_2.png")

this gives:

Note that you can use <sup> and <sub> in these labels to provide super- and subscripts.

Finally, if you have atom labels which should be displayed differently when the bond comes

into them from the right (the West), you can also set the _displayLabelW property:

>>> smi = 'c1nc(*)ccc1* |$;;;R1;;;;R2$|'

>>> mol = Chem.MolFromSmiles(smi)

>>> mol.GetAtomWithIdx(3).SetProp("_displayLabel","CO<sub>2</sub>H")

>>> mol.GetAtomWithIdx(3).SetProp("_displayLabelW","HO<sub>2</sub>C")

>>> mol.GetAtomWithIdx(7).SetProp("_displayLabel","CO<sub>2</sub><sup>-</sup>")

>>> mol.GetAtomWithIdx(7).SetProp("_displayLabelW","<sup>-</sup>OOC")

>>> d = rdMolDraw2D.MolDraw2DCairo(250, 250)

>>> rdMolDraw2D.PrepareAndDrawMolecule(d,mol)

>>> d.WriteDrawingText("./images/atom_labels_3.png")

this gives:

Metadata in Molecule Images¶

New in 2020.09 release

The PNG files generated by the MolDraw2DCairo class by default include metadata about the molecule(s) or chemical reaction included in the drawing. This metadata can be used later to reconstruct the molecule(s) or reaction.

>>> template = Chem.MolFromSmiles('c1nccc2n1ccc2')

>>> AllChem.Compute2DCoords(template)

0

>>> ms = [Chem.MolFromSmiles(smi) for smi in ('OCCc1ccn2cnccc12','C1CC1Oc1cc2ccncn2c1','CNC(=O)c1nccc2cccn12')]

>>> _ = [AllChem.GenerateDepictionMatching2DStructure(m,template) for m in ms]

>>> d = rdMolDraw2D.MolDraw2DCairo(250, 200)

>>> d.DrawMolecule(ms[0])

>>> d.FinishDrawing()

>>> png = d.GetDrawingText()

>>> mol = Chem.MolFromPNGString(png)

>>> Chem.MolToSmiles(mol)

'OCCc1c2ccncn2cc1'

The molecular metadata is stored using standard metadata tags in the PNG and is, of course, not visible when you look at the PNG:

If the PNG contains multiple molecules we can retrieve them all at once using Chem.MolsFromPNGString():

>>> from rdkit.Chem import Draw

>>> png = Draw.MolsToGridImage(ms,returnPNG=True)

>>> mols = Chem.MolsFromPNGString(png)

>>> for mol in mols:

... print(Chem.MolToSmiles(mol))

...

OCCc1c2ccncn2cc1

c1cc2cc(OC3CC3)cn2cn1

CNC(=O)c1nccc2cccn12

Substructure Searching¶

Substructure matching can be done using query molecules built from SMARTS:

>>> m = Chem.MolFromSmiles('c1ccccc1O')

>>> patt = Chem.MolFromSmarts('ccO')

>>> m.HasSubstructMatch(patt)

True

>>> m.GetSubstructMatch(patt)

(0, 5, 6)

Those are the atom indices in m, ordered as patt’s atoms. To get all of the matches:

>>> m.GetSubstructMatches(patt)

((0, 5, 6), (4, 5, 6))

This can be used to easily filter lists of molecules:

>>> patt = Chem.MolFromSmarts('c[NH1]')

>>> matches = []

>>> with Chem.SDMolSupplier('data/actives_5ht3.sdf') as suppl:

... for mol in suppl:

... if mol.HasSubstructMatch(patt):

... matches.append(mol)

>>> len(matches)

22

We can write the same thing more compactly using Python’s list comprehension syntax:

>>> with Chem.SDMolSupplier('data/actives_5ht3.sdf') as suppl:

... matches = [x for x in suppl if x.HasSubstructMatch(patt)]

>>> len(matches)

22

Substructure matching can also be done using molecules built from SMILES instead of SMARTS:

>>> m = Chem.MolFromSmiles('C1=CC=CC=C1OC')

>>> m.HasSubstructMatch(Chem.MolFromSmarts('CO'))

True

>>> m.HasSubstructMatch(Chem.MolFromSmiles('CO'))

True

But don’t forget that the semantics of the two languages are not exactly equivalent:

>>> m.HasSubstructMatch(Chem.MolFromSmiles('COC'))

True

>>> m.HasSubstructMatch(Chem.MolFromSmarts('COC'))

False

>>> m.HasSubstructMatch(Chem.MolFromSmarts('COc')) #<- need an aromatic C

True

Stereochemistry in substructure matches¶

By default information about stereochemistry is not used in substructure searches:

>>> m = Chem.MolFromSmiles('CC[C@H](F)Cl')

>>> m.HasSubstructMatch(Chem.MolFromSmiles('C[C@H](F)Cl'))

True

>>> m.HasSubstructMatch(Chem.MolFromSmiles('C[C@@H](F)Cl'))

True

>>> m.HasSubstructMatch(Chem.MolFromSmiles('CC(F)Cl'))

True

But this can be changed via the useChirality argument:

>>> m.HasSubstructMatch(Chem.MolFromSmiles('C[C@H](F)Cl'),useChirality=True)

True

>>> m.HasSubstructMatch(Chem.MolFromSmiles('C[C@@H](F)Cl'),useChirality=True)

False

>>> m.HasSubstructMatch(Chem.MolFromSmiles('CC(F)Cl'),useChirality=True)

True

Notice that when useChirality is set a non-chiral query does match a chiral molecule. The same is not true for a chiral query and a non-chiral molecule:

>>> m.HasSubstructMatch(Chem.MolFromSmiles('CC(F)Cl'))

True

>>> m2 = Chem.MolFromSmiles('CCC(F)Cl')

>>> m2.HasSubstructMatch(Chem.MolFromSmiles('C[C@H](F)Cl'),useChirality=True)

False

Atom Map Indices in SMARTS¶

It is possible to attach indices to the atoms in the SMARTS

pattern. This is most often done in reaction SMARTS (see Chemical

Reactions), but is more general than that. For example, in the

SMARTS patterns for torsion angle analysis published by Guba et al.

(DOI: acs.jcim.5b00522) indices are used to define the four atoms of

the torsion of interest. This allows additional atoms to be used to

define the environment of the four torsion atoms, as in

[cH0:1][c:2]([cH0])!@[CX3!r:3]=[NX2!r:4] for an aromatic C=N

torsion. We might wonder in passing why they didn’t use

recursive SMARTS for this, which would have made life easier, but it

is what it is. The atom lists from GetSubstructureMatches are

guaranteed to be in order of the SMARTS, but in this case we’ll get five

atoms so we need a way of picking out, in the correct order, the four of

interest. When the SMARTS is parsed, the relevant atoms are assigned an

atom map number property that we can easily extract:

>>> qmol = Chem.MolFromSmarts( '[cH0:1][c:2]([cH0])!@[CX3!r:3]=[NX2!r:4]' )

>>> ind_map = {}

>>> for atom in qmol.GetAtoms() :

... map_num = atom.GetAtomMapNum()

... if map_num:

... ind_map[map_num-1] = atom.GetIdx()

>>> ind_map

{0: 0, 1: 1, 2: 3, 3: 4}

>>> map_list = [ind_map[x] for x in sorted(ind_map)]

>>> map_list

[0, 1, 3, 4]

Then, when using the query on a molecule you can get the indices of the four matching atoms like this:

>>> mol = Chem.MolFromSmiles('Cc1cccc(C)c1C(C)=NC')

>>> for match in mol.GetSubstructMatches( qmol ) :

... mas = [match[x] for x in map_list]

... print(mas)

[1, 7, 8, 10]

Advanced substructure matching¶

Starting with the 2020.03 release, the RDKit allows you to provide an optional function that is used to check whether or not a possible substructure match should be accepted. This function is called with the molecule to be matched and the indices of the matching atoms.

Here’s an example of how you can use the functionality to do “Markush-like” matching, requiring that all atoms in a sidechain are either carbon (type “all_carbon”) or aren’t aromatic (type “alkyl”). We start by defining the class that we’ll use to test the sidechains:

from rdkit import Chem

class SidechainChecker(object):

matchers = {

'alkyl': lambda at: not at.GetIsAromatic(),

'all_carbon': lambda at: at.GetAtomicNum() == 6

}

def __init__(self, query, pName="queryType"):

# identify the atoms that have the properties we care about

self._atsToExamine = [(x.GetIdx(), x.GetProp(pName)) for x in query.GetAtoms()

if x.HasProp(pName)]

self._pName = pName

def __call__(self, mol, vect):

seen = [0] * mol.GetNumAtoms()

for idx in vect:

seen[idx] = 1

# loop over the atoms we care about:

for idx, qtyp in self._atsToExamine:

midx = vect[idx]

stack = [midx]

atom = mol.GetAtomWithIdx(midx)

# now do a breadth-first search from that atom, checking

# all of its neighbors that aren't in the substructure

# query:

stack = [atom]

while stack:

atom = stack.pop(0)

if not self.matchers[qtyp](atom):

return False

seen[atom.GetIdx()] = 1

for nbr in atom.GetNeighbors():

if not seen[nbr.GetIdx()]:

stack.append(nbr)

return True

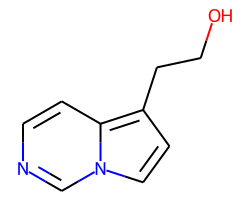

Here’s the molecule we’ll use:

And the default behavior:

>>> m = Chem.MolFromSmiles('C2NCC2CC1C(CCCC)C(OCCCC)C1c2ccccc2')

>>> p = Chem.MolFromSmarts('C1CCC1*')

>>> p.GetAtomWithIdx(4).SetProp("queryType", "all_carbon")

>>> m.GetSubstructMatches(p)

((5, 6, 11, 17, 18), (5, 17, 11, 6, 7), (6, 5, 17, 11, 12), (6, 11, 17, 5, 4))

Now let’s add the final check to filter the results:

>>> params = Chem.SubstructMatchParameters()

>>> checker = SidechainChecker(p)

>>> params.setExtraFinalCheck(checker)

>>> m.GetSubstructMatches(p,params)

((5, 6, 11, 17, 18), (5, 17, 11, 6, 7))

Repeat that using the ‘alkyl’ query:

>>> p.GetAtomWithIdx(4).SetProp("queryType", "alkyl")

>>> checker = SidechainChecker(p)

>>> params.setExtraFinalCheck(checker)

>>> m.GetSubstructMatches(p,params)

((5, 17, 11, 6, 7), (6, 5, 17, 11, 12), (6, 11, 17, 5, 4))

Chemical Transformations¶

The RDKit contains a number of functions for modifying molecules. Note that these transformation functions are intended to provide an easy way to make simple modifications to molecules. For more complex transformations, use the Chemical Reactions functionality.

Substructure-based transformations¶

There’s a variety of functionality for using the RDKit’s substructure-matching machinery for doing quick molecular transformations. These transformations include deleting substructures:

>>> m = Chem.MolFromSmiles('CC(=O)O')

>>> patt = Chem.MolFromSmarts('C(=O)[OH]')

>>> rm = AllChem.DeleteSubstructs(m,patt)

>>> Chem.MolToSmiles(rm)

'C'

replacing substructures:

>>> repl = Chem.MolFromSmiles('OC')

>>> patt = Chem.MolFromSmarts('[$(NC(=O))]')

>>> m = Chem.MolFromSmiles('CC(=O)N')

>>> rms = AllChem.ReplaceSubstructs(m,patt,repl)

>>> rms

(<rdkit.Chem.rdchem.Mol object at 0x...>,)

>>> Chem.MolToSmiles(rms[0])

'COC(C)=O'

as well as simple SAR-table transformations like removing side chains:

>>> m1 = Chem.MolFromSmiles('BrCCc1cncnc1C(=O)O')

>>> core = Chem.MolFromSmiles('c1cncnc1')

>>> tmp = Chem.ReplaceSidechains(m1,core)

>>> Chem.MolToSmiles(tmp)

'[1*]c1cncnc1[2*]'

and removing cores:

>>> tmp = Chem.ReplaceCore(m1,core)

>>> Chem.MolToSmiles(tmp)

'[1*]CCBr.[2*]C(=O)O'

By default the sidechains are labeled based on the order they are found. They can also be labeled according by the number of that core-atom they’re attached to:

>>> m1 = Chem.MolFromSmiles('c1c(CCO)ncnc1C(=O)O')

>>> tmp=Chem.ReplaceCore(m1,core,labelByIndex=True)

>>> Chem.MolToSmiles(tmp)

'[1*]CCO.[5*]C(=O)O'

rdkit.Chem.rdmolops.ReplaceCore() returns the sidechains in a single molecule.

This can be split into separate molecules using rdkit.Chem.rdmolops.GetMolFrags() :

>>> rs = Chem.GetMolFrags(tmp,asMols=True)

>>> len(rs)

2

>>> Chem.MolToSmiles(rs[0])

'[1*]CCO'

>>> Chem.MolToSmiles(rs[1])

'[5*]C(=O)O'

Murcko Decomposition¶

The RDKit provides standard Murcko-type decomposition [7] of molecules into scaffolds:

>>> from rdkit.Chem.Scaffolds import MurckoScaffold

>>> with Chem.SDMolSupplier('data/cdk2.sdf') as cdk2mols:

... m1 = cdk2mols[0]

>>> core = MurckoScaffold.GetScaffoldForMol(m1)

>>> Chem.MolToSmiles(core)

'c1ncc2nc[nH]c2n1'

or into a generic framework:

>>> fw = MurckoScaffold.MakeScaffoldGeneric(core)

>>> Chem.MolToSmiles(fw)

'C1CCC2CCCC2C1'

Maximum Common Substructure¶

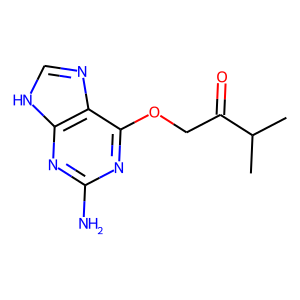

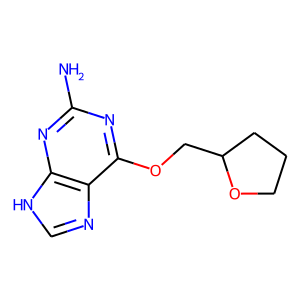

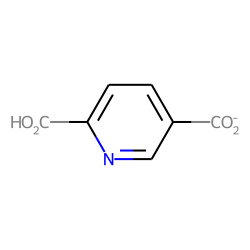

There are 2 methods for finding maximum common substructures. The first, FindMCS, finds a single fragment maximum common substructure (MCS) of two or more molecules: The second, RascalMCES, finds the maximum common edge substructure (MCES) between two molecules and can return a multi-fragment MCES. The difference is demonstrated with the following pair of molecules:

|

|

FMCS gives this maximum common substructure:

|

|

Whereas RascalMCES gives:

|

|

FindMCS¶

FindMCS operates on 2 or more molecules:

>>> from rdkit.Chem import rdFMCS

>>> mol1 = Chem.MolFromSmiles("O=C(NCc1cc(OC)c(O)cc1)CCCC/C=C/C(C)C")

>>> mol2 = Chem.MolFromSmiles("CC(C)CCCCCC(=O)NCC1=CC(=C(C=C1)O)OC")

>>> mol3 = Chem.MolFromSmiles("c1(C=O)cc(OC)c(O)cc1")

>>> mols = [mol1,mol2,mol3]

>>> res=rdFMCS.FindMCS(mols)

>>> res

<rdkit.Chem.rdFMCS.MCSResult object at 0x...>

>>> res.numAtoms

10

>>> res.numBonds

10

>>> res.smartsString

'[#6]1(-[#6]):[#6]:[#6](-[#8]-[#6]):[#6](:[#6]:[#6]:1)-[#8]'

>>> res.canceled

False

It returns an MCSResult instance with information about the number of

atoms and bonds in the MCS, the SMARTS string which matches the

identified MCS, and a flag saying if the algorithm timed out. If no

MCS is found then the number of atoms and bonds is set to 0 and the

SMARTS to ''.

By default, two atoms match if they are the same element and two bonds

match if they have the same bond type. Specify atomCompare and

bondCompare to use different comparison functions, as in:

>>> mols = (Chem.MolFromSmiles('NCC'),Chem.MolFromSmiles('OC=C'))

>>> rdFMCS.FindMCS(mols).smartsString

'[#6]'

>>> rdFMCS.FindMCS(mols, atomCompare=rdFMCS.AtomCompare.CompareAny).smartsString

'[#7,#8]-[#6]'

>>> rdFMCS.FindMCS(mols, bondCompare=rdFMCS.BondCompare.CompareAny).smartsString

'[#6]-,=[#6]'

The options for the atomCompare argument are: CompareAny says that any atom matches any other atom, CompareElements compares by element type, and CompareIsotopes matches based on the isotope label. Isotope labels can be used to implement user-defined atom types. A bondCompare of CompareAny says that any bond matches any other bond, CompareOrderExact says bonds are equivalent if and only if they have the same bond type, and CompareOrder allows single and aromatic bonds to match each other, but requires an exact order match otherwise:

>>> mols = (Chem.MolFromSmiles('c1ccccc1'),Chem.MolFromSmiles('C1CCCC=C1'))

>>> rdFMCS.FindMCS(mols,bondCompare=rdFMCS.BondCompare.CompareAny).smartsString

'[#6]1:,-[#6]:,-[#6]:,-[#6]:,-[#6]:,=[#6]:,-1'

>>> rdFMCS.FindMCS(mols,bondCompare=rdFMCS.BondCompare.CompareOrderExact).smartsString

'[#6]'

>>> rdFMCS.FindMCS(mols,bondCompare=rdFMCS.BondCompare.CompareOrder).smartsString

'[#6](:,-[#6]:,-[#6]:,-[#6]):,-[#6]:,-[#6]'

A substructure has both atoms and bonds. By default, the algorithm

attempts to maximize the number of bonds found. You can change this by

setting the maximizeBonds argument to False.

Maximizing the number of bonds tends to maximize the number of rings,

although two small rings may have fewer bonds than one large ring.

You might not want a 3-valent nitrogen to match one which is 5-valent.

The default matchValences value of False ignores valence

information. When True, the atomCompare setting is modified to also

require that the two atoms have the same valency.

>>> mols = (Chem.MolFromSmiles('NC1OC1'),Chem.MolFromSmiles('C1OC1[N+](=O)[O-]'))

>>> rdFMCS.FindMCS(mols).numAtoms

4

>>> rdFMCS.FindMCS(mols, matchValences=True).numBonds

3

It can be strange to see a linear carbon chain match a carbon ring,

which is what the ringMatchesRingOnly default of False does. If

you set it to True then ring bonds will only match ring bonds.

>>> mols = [Chem.MolFromSmiles("C1CCC1CCC"), Chem.MolFromSmiles("C1CCCCCC1")]

>>> rdFMCS.FindMCS(mols).smartsString

'[#6](-[#6]-[#6])-[#6]-[#6]-[#6]-[#6]'

>>> rdFMCS.FindMCS(mols, ringMatchesRingOnly=True).smartsString

'[#6&R](-&@[#6&R]-&@[#6&R])-&@[#6&R]'

Notice that the SMARTS returned now include ring queries on the atoms and bonds.

You can further restrict things and require that partial rings (as in

this case) are not allowed. That is, if an atom is part of the MCS and

the atom is in a ring of the entire molecule then that atom is also in

a ring of the MCS. Setting completeRingsOnly to True toggles this

requirement.

>>> mols = [Chem.MolFromSmiles("CCC1CC2C1CN2"), Chem.MolFromSmiles("C1CC2C1CC2")]

>>> rdFMCS.FindMCS(mols).smartsString

'[#6]1-[#6]-[#6](-[#6]-1-[#6])-[#6]'

>>> rdFMCS.FindMCS(mols, ringMatchesRingOnly=True).smartsString

'[#6]1-&@[#6]-&@[#6](-&@[#6]-&@1)-&@[#6&R]'

>>> rdFMCS.FindMCS(mols, completeRingsOnly=True).smartsString

'[#6]1-&@[#6]-&@[#6]-&@[#6]-&@1'

Of course the two options can be combined with each other:

>>> ms = [Chem.MolFromSmiles(x) for x in ('CC1CCC1','CCC1CC1',)]

>>> rdFMCS.FindMCS(ms,ringMatchesRingOnly=True).smartsString

'[#6&!R]-&!@[#6&R](-&@[#6&R])-&@[#6&R]'

>>> rdFMCS.FindMCS(ms,completeRingsOnly=True).smartsString

'[#6]-&!@[#6]'

>>> rdFMCS.FindMCS(ms,ringMatchesRingOnly=True,completeRingsOnly=True).smartsString

'[#6&!R]-&!@[#6&R]'

The MCS algorithm will exhaustively search for a maximum common substructure.

Typically this takes a fraction of a second, but for some comparisons this

can take minutes or longer. Use the timeout parameter to stop the search

after the given number of seconds (wall-clock seconds, not CPU seconds) and

return the best match found in that time. If timeout is reached then the

canceled property of the MCSResult will be True instead of False.

>>> mols = [Chem.MolFromSmiles("Nc1ccccc1"*10), Chem.MolFromSmiles("Nc1ccccccccc1"*10)]

>>> rdFMCS.FindMCS(mols, timeout=1).canceled

True

(The MCS after 50 seconds contained 511 atoms.)

RascalMCES¶

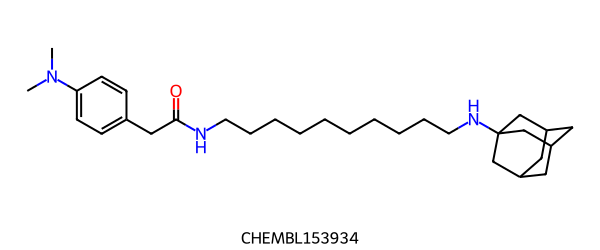

RascalMCES can only work on 2 molecules at a time:

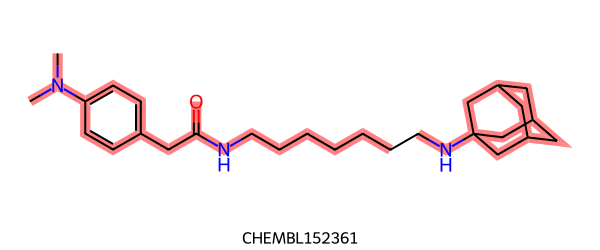

>>> from rdkit.Chem import rdRascalMCES

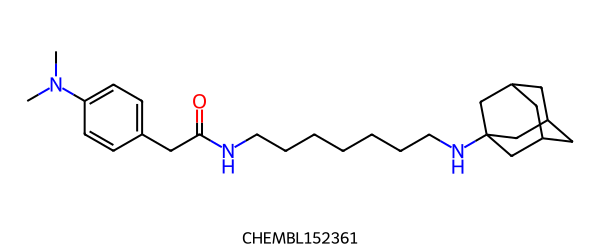

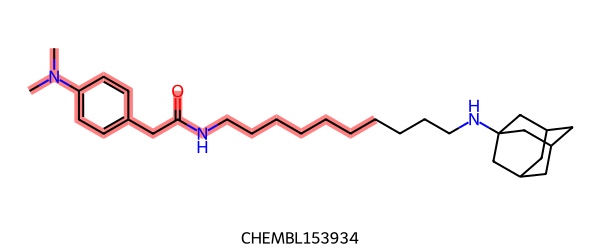

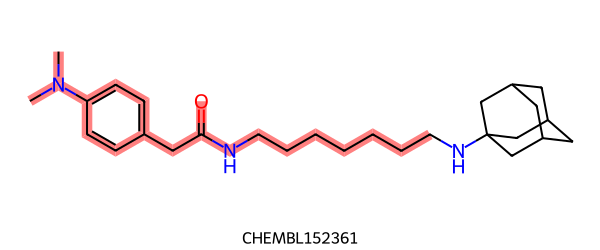

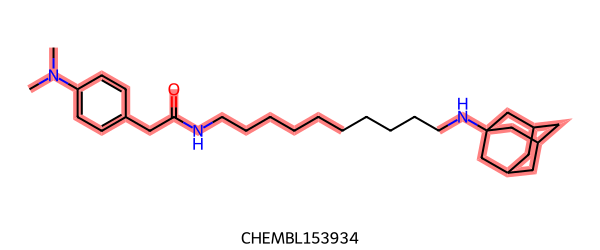

>>> mol1 = Chem.MolFromSmiles("CN(C)c1ccc(CC(=O)NCCCCCCCCCCNC23CC4CC(C2)CC(C3)C4)cc1 CHEMBL153934")

>>> mol2 = Chem.MolFromSmiles("CN(C)c1ccc(CC(=O)NCCCCCCCNC23CC4CC(C2)CC(C3)C4)cc1 CHEMBL152361")

>>> res = rdRascalMCES.FindMCES(mol1, mol2)

>>> res[0].smartsString

'CN(-C)-c1:c:c:c(-CC(=O)-NCCCCCCC):c:c:1.NC12CC3CC(-C1)-CC(-C2)-C3'

>>> len(res[0].bondMatches())

33

It returns a list of RascalResult objects. Each RascalResult contains the 2 molecules that the result pertains to, the SMARTS string of the MCES, the lists of atoms and bonds in the two molecules that match, the Johnson similarity between the 2 molecules, the number of fragments in the MCES, the number of atoms in the largest fragment and whether the run timed out or not. There is also the method largestFragmentOnly(), which cuts the MCES down to the largest single fragment. This is a non-reversible change, so if you want both results, take a copy first.

By default, the MCES algorithm returns the first result it finds of maximum size. Because of symmetry, there may be other equivalent solutions with the same number of atoms and bonds, but with different equivalent bonds matched to each other. If you want to see all MCESs of maximum size, you can use the option allBestMCESs = True. This will increase the run time, partly because more branches in the search tree must be examined, but mostly because sorting the multiple results is quite time-consuming. The results are returned in a consistent order sorted by number of bond matches, then number of fragments (fewer first), then largest fragment size and so on. Some of these aren’t trivial to compute. The adamantane example above is particularly extreme because not only is there extensive symmetry about the adamantane end and 2-fold symmetry at the phenyl end but also several points of breaking the matching alkyl chain all of which give rise to valid MCESs of the same size. In this case, sorting into a consistent order takes significantly longer than determining the MCESs in the first place.

The MCES differs from a conventional MCS in that it is the maximum common substructure based on bonds rather than atoms. Often the result is the same, but not always.

The Johnson similarity is akin to a Tanimoto similarity, but expressed in terms of the atoms and bonds in the MCES. It is the square of the sum of the number of atoms and bonds in the MCES divided by the product of the sums of the numbers of atoms and bonds in the 2 input molecules. It has values between 0.0 (no MCES between the molecules) and 1.0 (the molecules are identical). A key source of efficiency in the RASCAL algorithm is a fast and correct prediction of a maximum value for the Johnson similarity between 2 molecules and hence the maximum size of the MCES. The first step in the algorithm is then a screening, whereby the full MCES determination is not performed if the predicted similarity is less than some desired threshold. The final similarity between the 2 molecules may be less than the threshold, but it will never be higher than the predicted upper bound. RASCAL stems from RApid Similarity CALulation.

The default settings for RascalMCES are good for general use, but they may be altered by passing an optional RascalOptions object:

>>> mol1 = Chem.MolFromSmiles('Oc1cccc2C(=O)C=CC(=O)c12')

>>> mol2 = Chem.MolFromSmiles('O1C(=O)C=Cc2cc(OC)c(O)cc12')

>>> results = rdRascalMCES.FindMCES(mol1, mol2)

>>> len(results)

0

>>> opts = rdRascalMCES.RascalOptions()

>>> opts.similarityThreshold = 0.5

>>> results = rdRascalMCES.FindMCES(mol1, mol2, opts)

>>> len(results)

1

>>> f'{results[0].similarity:.2f}'

'0.37'

>>> results[0].smartsString

'Oc1:c:c:c:c:c:1.[#6]=O'

>>> opts.minFragSize = 3

>>> results = rdRascalMCES.FindMCES(mol1, mol2, opts)

>>> len(results)

1

>>> f'{results[0].similarity:.2f}'

'0.25'

>>> results[0].smartsString

'Oc1:c:c:c:c:c:1'

In this case, the upper bound on the similarity score is below the default threshold of 0.7, so no results are returned. Setting the threshold to 0.5 produces the second result although, as can be seen, the final similarity is substantially below the threshold. This example also shows a disadvantage of the MCES method, which is that it can produce small fragments in the MCES which are rarely helpful. The option minFragSize can be used to over-ride the default value of -1, which means no minimum size.

Like FindMCS, there is a ringMatchesRingOnly option, and also there’s completeAromaticRings, which is True by default, and means that MCESs won’t be returned with partial aromatic rings matching:

>>> mol1 = Chem.MolFromSmiles('C1CCCC1c1ccncc1')

>>> mol2 = Chem.MolFromSmiles('C1CCCC1c1ccccc1')

>>> results = rdRascalMCES.FindMCES(mol1, mol2, opts)

>>> f'{results[0].similarity:.2f}'

'0.27'

>>> results[0].smartsString

'C1CCCC1-c'

>>> opts.completeAromaticRings = False

>>> results = rdRascalMCES.FindMCES(mol1, mol2, opts)

>>> f'{results[0].similarity:.2f}'

'0.76'

>>> results[0].smartsString

'C1CCCC1-c(:c:c):c:c'

This result may look a bit odd, with a single aromatic carbon in the first SMARTS string. This is a consequence of the fact that the MCES works on matching bonds. A better, atom-centric, representation might be C1CCC[$(C-c)]1. When the completeAromaticRings option is set to False, a larger MCES is found, with just the pyridine nitrogen atom not matching the corresponding phenyl carbon atom.

Clustering with Rascal¶

There are 2 clustering methods available using the Johnson metric. The first, RascalCluster, is a fuzzy method described in ‘A Line Graph Algorithm for Clustering Chemical Structures Based on Common Substructural Cores’, JW Raymond, PW Willett (https://match.pmf.kg.ac.rs/electronic_versions/Match48/match48_197-207.pdf also available at https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/77598/). The second, RascalButinaCluster, uses the Butina sphere-exclusion algorithm (Butina JCICS 39 747-750 (1999)). Because of the time-consuming nature of the MCES determination, these clustering methods can be slow to run, so are best used on small sets (no more than a few hundred molecules) of small molecules.

Fingerprinting and Molecular Similarity¶

The RDKit has a variety of built-in functionality for generating molecular fingerprints and using them to calculate molecular similarity.

The most straightforward and consistent way to get fingerprints is to create a FingeprintGenerator object for your fingerprint type of interest and then use that to calculate fingerprints. Fingerprint generators provide a consistent interface to all the supported fingerprinting methods and allow easy generation of fingerprints as:

bit vectors :

fpgen.GetFingerprintsparse (unfolded) bit vectors :

fpgen.GetSparseFingerprintcount vectors :

fpgen.GetCountFingerprintsparse (unfolded) count vectors :

fpgen.GetSparseCountFingerprint

Note that there are older, legacy methods of generating fingerprints with the RDKit which are still supported, but these will not be covered here.

RDKit (Topological) Fingerprints¶

>>> from rdkit import DataStructs

>>> ms = [Chem.MolFromSmiles('CCOC'), Chem.MolFromSmiles('CCO'),

... Chem.MolFromSmiles('COC')]

>>> fpgen = AllChem.GetRDKitFPGenerator()

>>> fps = [fpgen.GetFingerprint(x) for x in ms]

>>> DataStructs.TanimotoSimilarity(fps[0],fps[1])

0.6...

>>> DataStructs.TanimotoSimilarity(fps[0],fps[2])

0.4...

>>> DataStructs.TanimotoSimilarity(fps[1],fps[2])

0.25

The examples above used Tanimoto similarity, but one can use different similarity metrics:

>>> DataStructs.DiceSimilarity(fps[0],fps[1])

0.75

Available similarity metrics include Tanimoto, Dice, Cosine, Sokal, Russel, Kulczynski, McConnaughey, and Tversky.

More details about the algorithm used for the RDKit fingerprint can be found in the “RDKit Book”.

The default set of parameters used by the fingerprinter is:

minimum path size: 1 bond

maximum path size: 7 bonds

fingerprint size: 2048 bits

number of bits set per hash: 2

You can control these when calling

AllChem.GetRDKitFPGenerator():

>>> fpgen = AllChem.GetRDKitFPGenerator(maxPath=2,fpSize=1024)

>>> fps = [fpgen.GetFingerprint(x) for x in ms]

>>> DataStructs.TanimotoSimilarity(fps[0],fps[2])

0.5

Atom Pairs and Topological Torsions¶

Atom-pair descriptors [3] are available in several different forms. The standard form is as fingerprint including counts for each bit instead of just zeros and ones:

>>> ms = [Chem.MolFromSmiles('C1CCC1OCC'),Chem.MolFromSmiles('CC(C)OCC'),Chem.MolFromSmiles('CCOCC')]

>>> fpgen = AllChem.GetAtomPairGenerator()

>>> pairFps = [fpgen.GetSparseCountFingerprint(x) for x in ms]

Because the space of bits that can be included in atom-pair fingerprints is huge, they are stored in a sparse manner. We can get the list of bits and their counts for each fingerprint as a dictionary:

>>> pairFps[-1].GetNonzeroElements()

{541732: 1, 558113: 2, 558115: 2, 558146: 1, 1606690: 2, 1606721: 2}

Unlike most other fingerprint types, descriptions of the bits are directly available:

>>> from rdkit.Chem.AtomPairs import Pairs

>>> Pairs.ExplainPairScore(558115)

(('C', 1, 0), 3, ('C', 2, 0))

The above means: C with 1 neighbor and 0 pi electrons which is 3 bonds from a C with 2 neighbors and 0 pi electrons

The usual metric for similarity between atom-pair fingerprints is Dice similarity:

>>> from rdkit import DataStructs

>>> DataStructs.DiceSimilarity(pairFps[0],pairFps[1])

0.333...

>>> DataStructs.DiceSimilarity(pairFps[0],pairFps[2])

0.258...

>>> DataStructs.DiceSimilarity(pairFps[1],pairFps[2])

0.56

It’s also possible to get atom-pair descriptors encoded as a standard bit vector fingerprint.

>>> pairFps = [fpgen.GetFingerprint(x) for x in ms]

>>> DataStructs.DiceSimilarity(pairFps[0],pairFps[1])

0.352...

>>> DataStructs.DiceSimilarity(pairFps[0],pairFps[2])

0.266...

>>> DataStructs.DiceSimilarity(pairFps[1],pairFps[2])

0.583...

By default the atom pair bit vector fingerprints use a scheme which simulates counts in the bit vectors (described in detail in the “RDKit Book”), but this can be disabled:

>>> fpgen = AllChem.GetAtomPairGenerator(countSimulation=False)

>>> pairFps = [fpgen.GetFingerprint(x) for x in ms]

>>> DataStructs.DiceSimilarity(pairFps[0],pairFps[1])

0.5

>>> DataStructs.DiceSimilarity(pairFps[0],pairFps[2])

0.4

>>> DataStructs.DiceSimilarity(pairFps[1],pairFps[2])

0.625

Topological torsion descriptors [4] are calculated in essentially the same way:

>>> fpgen = AllChem.GetTopologicalTorsionGenerator()

>>> tts = [fpgen.GetSparseCountFingerprint(x) for x in ms]

>>> DataStructs.DiceSimilarity(tts[0],tts[1])

0.166...

Topological torsion fingerprints, like atom-pair fingerprints, use a count simulation scheme by default when generating bit vector fingerprints

Morgan Fingerprints (Circular Fingerprints)¶

This family of fingerprints, better known as circular fingerprints [5], is built by applying the Morgan algorithm to a set of user-supplied atom invariants. When generating Morgan fingerprints, the radius of the fingerprint can also be provided (the default is 3):

>>> from rdkit.Chem import AllChem

>>> fpgen = AllChem.GetMorganGenerator(radius=2)

>>> m1 = Chem.MolFromSmiles('Cc1ccccc1')

>>> fp1 = fpgen.GetSparseCountFingerprint(m1)

>>> fp1

<rdkit.DataStructs.cDataStructs.ULongSparseIntVect object at 0x...>

>>> m2 = Chem.MolFromSmiles('Cc1ncccc1')

>>> fp2 = fpgen.GetSparseCountFingerprint(m2)

>>> DataStructs.DiceSimilarity(fp1,fp2)

0.55...

Morgan fingerprints, like atom pairs and topological torsions, are often used as counts, but it’s also possible to calculate them as bit vectors, the default fingerprint size is 2048 bits:

>>> fp1 = fpgen.GetFingerprint(m1)

>>> fp1

<rdkit.DataStructs.cDataStructs.ExplicitBitVect object at 0x...>

>>> len(fp1)

2048

>>> fp2 = fpgen.GetFingerprint(m2)

>>> DataStructs.DiceSimilarity(fp1,fp2)

0.51...

The default atom invariants use connectivity information similar to those used for the well known ECFP family of fingerprints. Feature-based invariants, similar to those used for the FCFP fingerprints, can also be used by creating the fingerprint generator with an appropriate atom invariant generator. The feature definitions used are defined in the section Feature Definitions Used in the Morgan Fingerprints. At times this can lead to quite different similarity scores:

>>> m1 = Chem.MolFromSmiles('c1ccccn1')

>>> m2 = Chem.MolFromSmiles('c1ccco1')

>>> fpgen = AllChem.GetMorganGenerator(radius=2)

>>> fp1 = fpgen.GetSparseCountFingerprint(m1)

>>> fp2 = fpgen.GetSparseCountFingerprint(m2)

>>> invgen = AllChem.GetMorganFeatureAtomInvGen()

>>> ffpgen = AllChem.GetMorganGenerator(radius=2, atomInvariantsGenerator=invgen)

>>> ffp1 = ffpgen.GetSparseCountFingerprint(m1)

>>> ffp2 = ffpgen.GetSparseCountFingerprint(m2)

>>> DataStructs.DiceSimilarity(fp1,fp2)

0.36...

>>> DataStructs.DiceSimilarity(ffp1,ffp2)

0.90...

When comparing the ECFP/FCFP fingerprints and the Morgan fingerprints generated by the RDKit, remember that the 4 in ECFP4 corresponds to the diameter of the atom environments considered, while the Morgan fingerprints take a radius parameter. So the examples above, with radius=2, are roughly equivalent to ECFP4 and FCFP4.

The user can also provide their own atom invariants using the optional

customAtomInvariants argument to the GetFingerprint() call. Here’s a

simple example that uses a constant for the invariant; the resulting

fingerprints compare the topology of molecules:

>>> m1 = Chem.MolFromSmiles('Cc1ccccc1')

>>> m2 = Chem.MolFromSmiles('Cc1ncncn1')

>>> fpgen = AllChem.GetMorganGenerator(radius=2)

>>> fp1 = fpgen.GetFingerprint(m1,customAtomInvariants=[1]*m1.GetNumAtoms())

>>> fp2 = fpgen.GetFingerprint(m2,customAtomInvariants=[1]*m2.GetNumAtoms())

>>> fp1==fp2

True

Note that bond order is by default still considered:

>>> m3 = Chem.MolFromSmiles('CC1CCCCC1')

>>> fp3 = fpgen.GetFingerprint(m3,customAtomInvariants=[1]*m3.GetNumAtoms())

>>> fp1==fp3

False

But this can also be turned off:

>>> fpgen = AllChem.GetMorganGenerator(radius=2,useBondTypes=False)

>>> fp1 = fpgen.GetFingerprint(m1,customAtomInvariants=[1]*m1.GetNumAtoms())

>>> fp3 = fpgen.GetFingerprint(m3,customAtomInvariants=[1]*m3.GetNumAtoms())

>>> fp1==fp3

True

MACCS Keys¶

There is a SMARTS-based implementation of the 166 public MACCS keys. This is not currently supported by the RDKit’s fingerprint generators, so you have to use a different interface.

>>> from rdkit.Chem import MACCSkeys

>>> ms = [Chem.MolFromSmiles('CCOC'), Chem.MolFromSmiles('CCO'),

... Chem.MolFromSmiles('COC')]

>>> fps = [MACCSkeys.GenMACCSKeys(x) for x in ms]

>>> DataStructs.TanimotoSimilarity(fps[0],fps[1])

0.5

>>> DataStructs.TanimotoSimilarity(fps[0],fps[2])

0.538...

>>> DataStructs.TanimotoSimilarity(fps[1],fps[2])

0.214...

The MACCS keys were critically evaluated and compared to other MACCS implementations in Q3 2008. In cases where the public keys are fully defined, things looked pretty good.

Explaining bits from fingerprints¶

The fingerprint generators can collect information about the atoms/bonds involved in setting bits when a fingerprint is generated. This information is quite useful for understanding which parts of a molecule were involved in each bit.

Each fingerprinting method provides different information, but this is all accessed using the additionalOutput argument to the fingerprinting functions.

Morgan Fingerprints¶

Information is available about the atoms that contribute to particular bits in the Morgan fingerprint via the bit info map. This is a dictionary with one entry per bit set in the fingerprint, the keys are the bit ids, the values are lists of (atom index, radius) tuples.

>>> m = Chem.MolFromSmiles('c1cccnc1C')

>>> fpgen = AllChem.GetMorganGenerator(radius=2)

>>> ao = AllChem.AdditionalOutput()

>>> ao.CollectBitInfoMap()

>>> fp = fpgen.GetSparseCountFingerprint(m,additionalOutput=ao)

>>> len(fp.GetNonzeroElements())

16

>>> info = ao.GetBitInfoMap()

>>> len(info)

16

>>> info[98513984]

((1, 1), (2, 1))

>>> info[4048591891]

((5, 2),)

Interpreting the above: bit 98513984 is set twice: once by atom 1 and once by atom 2, each at radius 1. Bit 4048591891 is set once by atom 5 at radius 2.

Focusing on bit 4048591891, we can extract the submolecule consisting of all atoms within a radius of 2 of atom 5:

>>> env = Chem.FindAtomEnvironmentOfRadiusN(m,2,5)

>>> amap={}

>>> submol=Chem.PathToSubmol(m,env,atomMap=amap)

>>> submol.GetNumAtoms()

6

>>> amap

{0: 0, 1: 1, 3: 2, 4: 3, 5: 4, 6: 5}

And then “explain” the bit by generating SMILES for that submolecule:

>>> Chem.MolToSmiles(submol)

'ccc(C)nc'

This is more useful when the SMILES is rooted at the central atom:

>>> Chem.MolToSmiles(submol,rootedAtAtom=amap[5],canonical=False)

'c(cc)(nc)C'

An alternate (and faster, particularly for large numbers of molecules)

approach to do the same thing, using the function rdkit.Chem.MolFragmentToSmiles() :

>>> atoms=set()

>>> for bidx in env:

... atoms.add(m.GetBondWithIdx(bidx).GetBeginAtomIdx())

... atoms.add(m.GetBondWithIdx(bidx).GetEndAtomIdx())

...

>>> Chem.MolFragmentToSmiles(m,atomsToUse=list(atoms),bondsToUse=env,rootedAtAtom=5)

'c(C)(cc)nc'

RDKit Fingerprints¶

Information is available about the bond paths that contribute to particular bits in the RDKit fingerprint via the bit info map. This is a dictionary with one entry per bit set in the fingerprint, the keys are the bit ids, the values are tuples of tuples containing bond indices.

>>> m = Chem.MolFromSmiles('CCO')

>>> fpgen = AllChem.GetRDKitFPGenerator()

>>> ao = AllChem.AdditionalOutput()

>>> ao.CollectBitPaths()

>>> fp = fpgen.GetSparseCountFingerprint(m,additionalOutput=ao)

>>> len(fp.GetNonzeroElements())

6

>>> paths = ao.GetBitPaths()

>>> len(paths)

6

>>> paths[54413874]

((1,),)

>>> paths[1135572127]

((0, 1),)

>>> paths[1524090560]

((0, 1),)

Those last two examples, which each correspond to the path containing bonds 0 and 1, demonstrate that by default each path sets two bits in the RDKit fingerprint. We can, of course, create a fingerprint generator which does not do this:

>>> fpgen = AllChem.GetRDKitFPGenerator(numBitsPerFeature=1)

>>> ao = AllChem.AdditionalOutput()

>>> ao.CollectBitPaths()

>>> fp = fpgen.GetSparseCountFingerprint(m,additionalOutput=ao)

>>> len(fp.GetNonzeroElements())

3

>>> ao.GetBitPaths()

{1524090560: ((0, 1),), 4274652475: ((1,),), 4275705116: ((0,),)}

Here we can also use the bond path information to create submolecules:

>>> envs = ao.GetBitPaths()[4274652475]

>>> envs

((1,),)

>>> env = envs[0]

>>> atoms=set()

>>> for bidx in env:

... atoms.add(m.GetBondWithIdx(bidx).GetBeginAtomIdx())

... atoms.add(m.GetBondWithIdx(bidx).GetEndAtomIdx())

...

>>> Chem.MolFragmentToSmiles(m,atomsToUse=list(atoms),bondsToUse=env)

'CO'

Generating images of fingerprint bits¶

For the Morgan and RDKit fingerprint types, it’s possible to generate images of

the atom environment that defines the bit using the functions

rdkit.Chem.Draw.DrawMorganBit() and rdkit.Chem.Draw.DrawRDKitBit()

>>> from rdkit.Chem import Draw

>>> mol = Chem.MolFromSmiles('c1ccccc1CC1CC1')

>>> fpgen = AllChem.GetMorganGenerator(radius=2)

>>> ao = AllChem.AdditionalOutput()

>>> ao.CollectBitInfoMap()

>>> fp = fpgen.GetFingerprint(mol,additionalOutput=ao)

>>> bi = ao.GetBitInfoMap()

>>> bi[872]

((6, 2),)

>>> mfp2_svg = Draw.DrawMorganBit(mol, 872, bi, useSVG=True)

>>> fpgen = AllChem.GetRDKitFPGenerator()

>>> ao = AllChem.AdditionalOutput()

>>> ao.CollectBitPaths()

>>> fp = fpgen.GetFingerprint(mol,additionalOutput=ao)

>>> rdkbi = ao.GetBitPaths()

>>> rdkbi[1553]

((0, 1, 9, 5, 4), (2, 3, 4, 9, 5))

>>> rdk_svg = Draw.DrawRDKitBit(mol, 1553, rdkbi, useSVG=True)

Producing these images:

Morgan bit |

RDKit bit |

The default highlight colors for the Morgan bits indicate:

blue: the central atom in the environment

yellow: aromatic atoms

gray: aliphatic ring atoms

The default highlight colors for the RDKit bits indicate:

yellow: aromatic atoms

Note that in cases where the same bit is set by multiple atoms in the molecule (as for bit 1553 for the RDKit fingerprint in the example above), the drawing functions will display the first example. You can change this by specifying which example to show:

>>> rdk_svg = Draw.DrawRDKitBit(mol, 1553, rdkbi, whichExample=1, useSVG=True)

Producing this image:

RDKit bit |

Picking Diverse Molecules Using Fingerprints¶

A common task is to pick a small subset of diverse molecules from a larger set.

The RDKit provides a number of approaches for doing this in the

rdkit.SimDivFilters module. The most efficient of these uses the

MaxMin algorithm. [6] Here’s an example:

Start by reading in a set of molecules and generating Morgan fingerprints:

>>> from rdkit import Chem

>>> from rdkit.Chem import rdFingerprintGenerator

>>> fpgen = rdFingerprintGenerator.GetMorganGenerator(radius=3)

>>> from rdkit import DataStructs

>>> from rdkit.SimDivFilters.rdSimDivPickers import MaxMinPicker

>>> with Chem.SDMolSupplier('data/actives_5ht3.sdf') as suppl:

... ms = [x for x in suppl if x is not None]

>>> fps = [fpgen.GetFingerprint(x) for x in ms]

>>> nfps = len(fps)

Now create a picker and grab a set of 10 diverse molecules:

>>> picker = MaxMinPicker()

>>> pickIndices = picker.LazyBitVectorPick(fps,nfps,10,seed=23)

>>> list(pickIndices)

[93, 137, 135, 109, 18, 150, 142, 12, 6, 160]

Note that the picker just returns indices of the fingerprints; we can get the molecules themselves as follows:

>>> picks = [ms[x] for x in pickIndices]

If we aren’t working with bit vector fingerprints, we can also do a diversity pick by providing our own distance matrix to the algorithm. This is less efficient than the above approach, but still works quite quickly:

>>> fps = [fpgen.GetSparseCountFingerprint(x) for x in ms]

>>> def distij(i,j,fps=fps):

... return 1-DataStructs.DiceSimilarity(fps[i],fps[j])

>>> picker = MaxMinPicker()

>>> pickIndices = picker.LazyPick(distij,nfps,10,seed=23)

>>> list(pickIndices)

[93, 109, 154, 6, 95, 135, 151, 61, 137, 139]

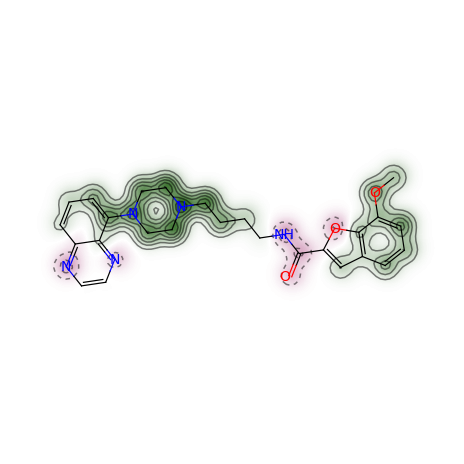

Generating Similarity Maps Using Fingerprints¶

Similarity maps are a way to visualize the atomic contributions to

the similarity between a molecule and a reference molecule. The

methodology is described in Ref. [17] .

They are in the rdkit.Chem.Draw.SimilarityMaps module :

Start by creating two molecules:

>>> from rdkit import Chem

>>> mol = Chem.MolFromSmiles('COc1cccc2cc(C(=O)NCCCCN3CCN(c4cccc5nccnc54)CC3)oc21')

>>> refmol = Chem.MolFromSmiles('CCCN(CCCCN1CCN(c2ccccc2OC)CC1)Cc1ccc2ccccc2c1')

The SimilarityMaps module supports three kind of fingerprints: atom pairs, topological torsions and Morgan fingerprints.

>>> from rdkit.Chem import Draw

>>> from rdkit.Chem.Draw import SimilarityMaps

>>> fp = SimilarityMaps.GetAPFingerprint(mol, fpType='normal')

>>> fp = SimilarityMaps.GetTTFingerprint(mol, fpType='normal')

>>> fp = SimilarityMaps.GetMorganFingerprint(mol, fpType='bv')

The types of atom pairs and torsions are normal (default), hashed and bit vector (bv). The types of the Morgan fingerprint are bit vector (bv, default) and count vector (count).

The function generating a similarity map for two fingerprints requires the specification of the fingerprint function and optionally the similarity metric. The default for the latter is the Dice similarity. Using all the default arguments of the Morgan fingerprint function, the similarity map can be generated like this:

>>> d2d = Draw.MolDraw2DCairo(400, 400)

>>> _, maxweight = SimilarityMaps.GetSimilarityMapForFingerprint(refmol, mol, SimilarityMaps.GetMorganFingerprint, d2d)

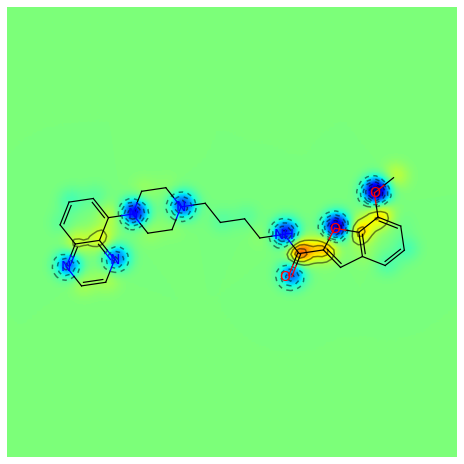

Producing this image:

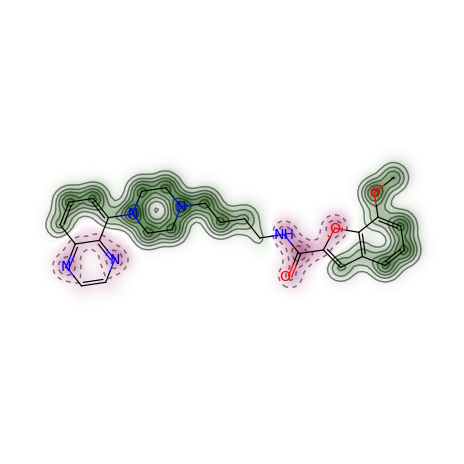

For a different type of Morgan (e.g. count) and radius = 1 instead of 2, as well as a different similarity metric (e.g. Tanimoto), the call becomes:

>>> from rdkit import DataStructs

>>> _, maxweight = SimilarityMaps.GetSimilarityMapForFingerprint(refmol, mol, lambda m,idx: SimilarityMaps.GetMorganFingerprint(m, atomId=idx, radius=1, fpType='count'), d2d, metric=DataStructs.TanimotoSimilarity)

Producing this image:

The convenience function GetSimilarityMapForFingerprint involves the normalisation of the atomic weights such that the maximum absolute weight is 1. Therefore, the function outputs the maximum weight that was found when creating the map.

>>> print(maxweight)

0.05747...

If one does not want the normalisation step, the map can be created like:

>>> weights = SimilarityMaps.GetAtomicWeightsForFingerprint(refmol, mol, SimilarityMaps.GetMorganFingerprint)

>>> print(["%.2f " % w for w in weights])

['0.05 ', ...

>>> _ = SimilarityMaps.GetSimilarityMapFromWeights(mol, weights, d2d)

Producing this image:

Descriptor Calculation¶

A variety of descriptors are available within the RDKit. The complete list is provided in List of Available Descriptors.

Most of the descriptors are straightforward to use from Python via the

centralized rdkit.Chem.Descriptors module :

>>> from rdkit.Chem import Descriptors

>>> m = Chem.MolFromSmiles('c1ccccc1C(=O)O')

>>> Descriptors.TPSA(m)

37.3

>>> Descriptors.MolLogP(m)

1.3848

Calculating All Descriptors¶

The rdkit.Chem.Descriptors module provides a convenience function, CalcMolDescriptors(), to calculate all available descriptors for a molecule. CalcMolDescriptors() returns a dictionary with descriptor names as the keys and descriptor values as the values:

>>> vals = Descriptors.CalcMolDescriptors(m)

>>> vals['TPSA']

37.3

>>> vals['NumHDonors']

1

CalcMolDescriptors() makes it easy to generate descriptors for a set of molecules and get the values into a pandas DataFrame:

>>> descrs = [Descriptors.CalcMolDescriptors(mol) for mol in mols] >>> df = pandas.DataFrame(descrs) >>> df.head() >>> df.head(3) MaxEStateIndex MinEStateIndex MaxAbsEStateIndex ... fr_thiophene fr_unbrch_alkane fr_urea 0 8.361111 -0.115741 8.361111 ... 0 0 0 1 8.361111 -0.115741 8.361111 ... 0 0 0 2 8.334769 0.329861 8.334769 ... 0 0 0[3 rows x 208 columns]

Calculating Partial Charges¶

Partial charges are handled a bit differently:

>>> m = Chem.MolFromSmiles('c1ccccc1C(=O)O')

>>> AllChem.ComputeGasteigerCharges(m)

>>> m.GetAtomWithIdx(0).GetDoubleProp('_GasteigerCharge')

-0.047...

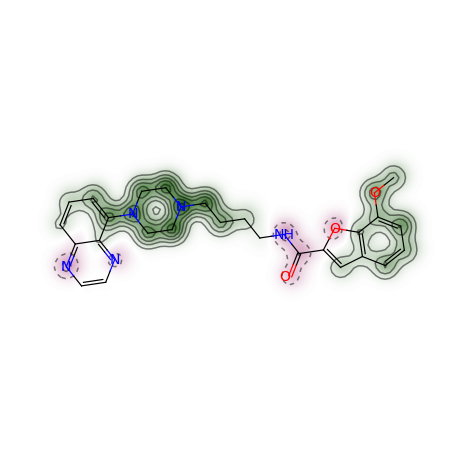

Visualization of Descriptors¶

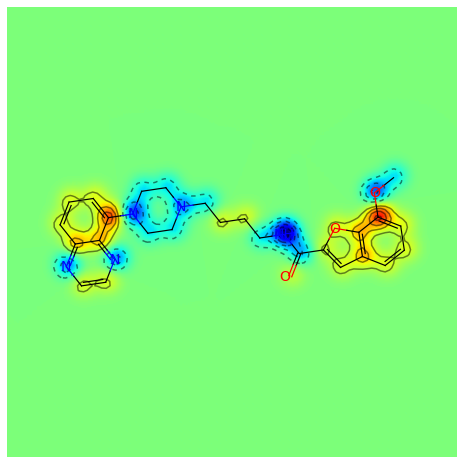

Similarity maps can be used to visualize descriptors that can be divided into atomic contributions.

The Gasteiger partial charges can be visualized as (using a different color scheme):

>>> from rdkit.Chem import Draw

>>> from rdkit.Chem.Draw import SimilarityMaps

>>> mol = Chem.MolFromSmiles('COc1cccc2cc(C(=O)NCCCCN3CCN(c4cccc5nccnc54)CC3)oc21')

>>> AllChem.ComputeGasteigerCharges(mol)

>>> contribs = [mol.GetAtomWithIdx(i).GetDoubleProp('_GasteigerCharge') for i in range(mol.GetNumAtoms())]

>>> d2d = Draw.MolDraw2DCairo(400, 400)

>>> _ = SimilarityMaps.GetSimilarityMapFromWeights(mol, contribs, d2d, colorMap='jet', contourLines=10)

Producing this image:

Or for the Crippen contributions to logP:

>>> from rdkit.Chem import rdMolDescriptors

>>> contribs = rdMolDescriptors._CalcCrippenContribs(mol)

>>> _ = SimilarityMaps.GetSimilarityMapFromWeights(mol,[x for x,y in contribs], d2d, colorMap='jet', contourLines=10)

Producing this image:

Chemical Reactions¶

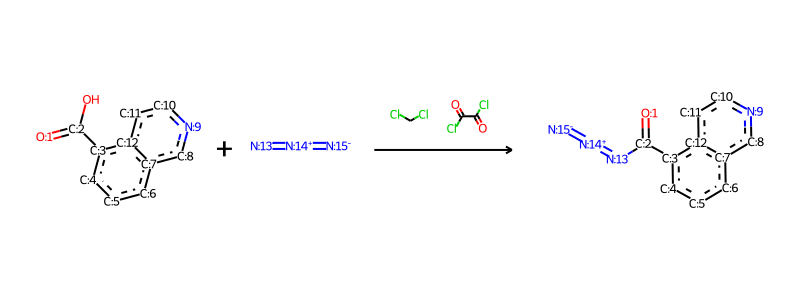

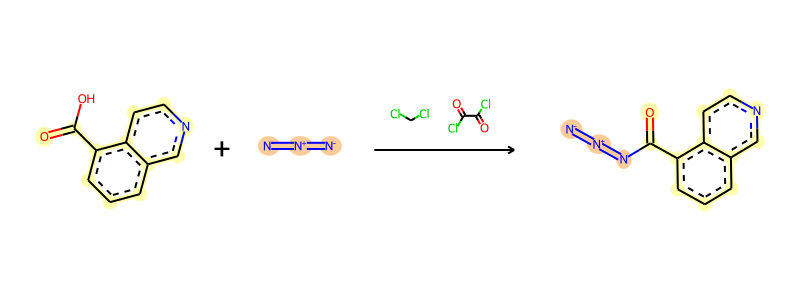

The RDKit also supports applying chemical reactions to sets of molecules. One way of constructing chemical reactions is to use a SMARTS-based language similar to Daylight’s Reaction SMILES [11]:

>>> rxn = AllChem.ReactionFromSmarts('[C:1](=[O:2])-[OD1].[N!H0:3]>>[C:1](=[O:2])[N:3]')

>>> rxn

<rdkit.Chem.rdChemReactions.ChemicalReaction object at 0x...>

>>> rxn.GetNumProductTemplates()

1

>>> ps = rxn.RunReactants((Chem.MolFromSmiles('CC(=O)O'),Chem.MolFromSmiles('NC')))

>>> len(ps) # one entry for each possible set of products

1

>>> len(ps[0]) # each entry contains one molecule for each product

1

>>> Chem.MolToSmiles(ps[0][0])

'CNC(C)=O'

>>> ps = rxn.RunReactants((Chem.MolFromSmiles('C(COC(=O)O)C(=O)O'),Chem.MolFromSmiles('NC')))

>>> len(ps)

2

>>> Chem.MolToSmiles(ps[0][0])

'CNC(=O)OCCC(=O)O'

>>> Chem.MolToSmiles(ps[1][0])

'CNC(=O)CCOC(=O)O'

Reactions can also be built from MDL rxn files:

>>> rxn = AllChem.ReactionFromRxnFile('data/AmideBond.rxn')

>>> rxn.GetNumReactantTemplates()

2

>>> rxn.GetNumProductTemplates()

1

>>> ps = rxn.RunReactants((Chem.MolFromSmiles('CC(=O)O'), Chem.MolFromSmiles('NC')))

>>> len(ps)

1

>>> Chem.MolToSmiles(ps[0][0])

'CNC(C)=O'

It is, of course, possible to do reactions more complex than amide bond formation:

>>> rxn = AllChem.ReactionFromSmarts('[C:1]=[C:2].[C:3]=[*:4][*:5]=[C:6]>>[C:1]1[C:2][C:3][*:4]=[*:5][C:6]1')

>>> ps = rxn.RunReactants((Chem.MolFromSmiles('OC=C'), Chem.MolFromSmiles('C=CC(N)=C')))

>>> Chem.MolToSmiles(ps[0][0])

'NC1=CCCC(O)C1'

Note in this case that there are multiple mappings of the reactants onto the templates, so we have multiple product sets:

>>> len(ps)

4

You can use canonical smiles and a python dictionary to get the unique products:

>>> uniqps = {}

>>> for p in ps: